Battle Of Brice’s Cross Roads, Or Tishomingo Creek, June 2nd to 12th, 1864

By Stephen D. Lee

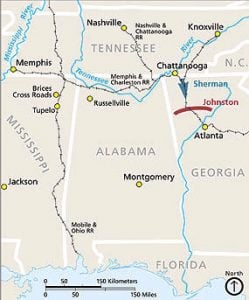

The campaign of Gen. Sherman, with his infantry command, from Vicksburg to Meridian, Miss. (February 3rd to March 5th, 1864), and his cavalry column, under Gen. William Sooy Smith, from Colliersville, Tenn., to West Point, Miss., (February nth to February 26th, 1864), left the two cavalry divisions of Generals S. D. Lee and N. B. Forrest much worn by excessive fatigue in marching and fighting continuously for over a month. The close of the campaign found Gen. Lee’s division in the vicinity of Canton, Miss., resting and recruiting, and Gen. Forrest’s command in the prairie region of Northeast Mississippi, near Okolona and Tupelo.

The great campaign in North Georgia between Gen. Sherman on the Union side and Gen. Joseph E. Johnston or. the Confederate side was about beginning, and troops were being sent to reinforce Gen. Johnston from Mississippi and other states of the Confederacy. As early as April 10th, Gen. Lee was ordered with part of his division from Canton, Miss., to Tuscaloosa, Ala., with the command of W. H. Jackson’s two brigades and of Ferguson’s brigade. On April 13th, Gen. Lee was put in command of all the cavalry in the Department of Mississippi, Alabama, East Louisiana, and West Tennessee, including Gen. Forrest’s command. On May 4, Gen. Lee’s own division was moved to Montevallo, Ala., to be nearer Gen. Johnston’s army. On the 9th day of May, Gen. Polk with two infantry divisions (Loring’s and French’s), which had been assigned to the defense of Mississippi, were sent to reinforce Gen. Johnston’s army.

Gen. S. D. Lee was relieved of the personal command of his cavalry division, which was also sent to report to Gen. Johnston, while he was ordered to relieve Gen. Polk of the command of his department: viz., Mississippi, Alabama, East Louisiana, and West Tennessee.

This disposition of troops took all the infantry out of the department except the small garrison left in Mobile for its defense.

Small garrisons (mainly for post duty), cavalry and artillery, were also left at Meridian, Miss., Selma, Ala., and a few paroled men at Enterprise, Miss., to protect public property at those places. The cavalry consisted of the recently organized command of Gen. Forrest in North Mississippi, only partially armed, of Adams’ brigade between Jackson and Vicksburg, Miss., of Roddey’s cavalry in North Alabama, and of Gholson’s brigade of state cavalry in Mississippi. The effective force was about 16,000 men, scattered along the river front from Louisiana to Memphis, and along the northern frontier of Mississippi and Alabama, from Memphis, Tenn., to Georgia. Opposed to this force of cavalry were large garrisons of infantry and cavalry at Baton Rogue, La., Vicksburg, Miss., Memphis, Tenn., and in North Alabama (mainly at Decatur) making constant raids into the interior from those localities.

As Gen. Sherman gradually pressed Gen. Johnston’s army back from Dalton, Ga., towards Atlanta, the railroads in Mississippi, connecting the prairie, or corn region, with Meridian ; the railroads from Meridian through Selma and Montgomery, Ala., to Atlanta, Ga., which mainly supplied Gen. Johnston’s army in North Georgia with provisions ; and the machinery and shops at Selma and Montgomery, Ala., for the manufacture of ordnance, harnesses, and ammunition, were a constant source of uneasiness to Gen. S. D. Lee and to the authorities at Richmond, Va., for fear of raids and large expeditions from North Alabama into the interior of the State to Selma or Montgomery.

Great pressure was brought to bear on Gen. Lee by Gen. Johnston and through Gen. Polk to have him move all his disposable cavalry force from Mississippi into Alabama to protect the flank of Johnston’s army and the immediate source of supplies for that army, or to virtually abandon the State of Mississippi to raids and move into Middle Tennessee to operate on and break up the railroads supplying Sherman’s army confronting Gen. Johnston.

In response to this constant pressure, Gen. Lee (May 22nd) moved one of Gen. Forrest’s cavalry divisions under Gen. Chalmers from Tupelo, Miss., to Montevallo, Ala., as the enemy had concentrated a force of 8,000 men at Decatur apparently to move into Middle Alabama. This Federal force was so threatening that on May 3ist, in response to most urgent appeals, Gen. Lee ordered Gen. Forrest to move with his other division of cavalry from Tupelo, Miss., into North Alabama to aid Generals Roddey and Chalmers in checking this force, as it was reported to be moving towards Montgomery. The column, however, turned eastward and reinforced Gen. Sherman in North Georgia.

In response to this constant pressure, Gen. Lee (May 22nd) moved one of Gen. Forrest’s cavalry divisions under Gen. Chalmers from Tupelo, Miss., to Montevallo, Ala., as the enemy had concentrated a force of 8,000 men at Decatur apparently to move into Middle Alabama. This Federal force was so threatening that on May 3ist, in response to most urgent appeals, Gen. Lee ordered Gen. Forrest to move with his other division of cavalry from Tupelo, Miss., into North Alabama to aid Generals Roddey and Chalmers in checking this force, as it was reported to be moving towards Montgomery. The column, however, turned eastward and reinforced Gen. Sherman in North Georgia.

Gen. Forrest had scarcely reached Russellville, Ala., when a large force of 8,000 men under Gen. Sturgis left the Memphis and Charleston railroad (just over the Mississippi border) near Saulsbury, Tenn. They were headed for the prairie region of Mississippi, and for Columbus, Miss., and Selma, Ala. This was a well organized force intended to defeat and crush Forrest as shown by the dispatches. Gen. Lee at once recalled Forrest from Alabama to meet this formidable invasion of Mississippi. That energetic officer returned with only one of his divisions and a part of Gen. Roddey ‘s force, leaving Gen. Chalmers still in Alabama to protect the interior of the State and the roads and the shops.

As previously stated, in consequence of the recent expeditions of Gen. Forrest into West Tennessee, a large Federal force was kept constantly at Memphis, Tenn., for the purpose of threatening Mississippi. Gen. Sturgis with a large force had followed Gen. Forrest out of Tennessee, and had pursued him as far south as Ripley, about May 10th, returning thence to Memphis. Gen. Lee was being pressed to send Gen. Forrest into Middle Tennessee, and had arranged to do so about the 17th of May. The column was about starting when definite information was acquired of a large force in Memphis, organizing to march against Forrest on the M. & O. Railroad. This caused Gen. Lee to suspend the movement upon the advice of Gen. Forrest. On May 22nd a large force at Decatur, Ala., threatened the shops and railroads at Montgomery and Selma and one of Gen. Forrest’s divisions under Gen. Chalmers was sent to Montevallo, Ala., to meet any emergency from that source.

The delay in starting the expedition from Memphis caused Gen. Forrest to believe it was not coming; and in his telegram of May 20th (p. 628, Serial Number No. 78 Rebellion Records) he said that, “The time has arrived, if I can be spared and allowed 2,000 picked men from Buford’s division, will attempt to cut enemies communication in Middle Tennessee.” But the movement of a column of 8,000 men from Decatur, Ala., southward, which proved to be a feint in favor of Gen. Sturgis, caused Gen. Lee (May 31st) to order Gen. Forrest to move with “his disposable force” to help Gen. Roddey in resisting this column. Gen. Forrest left Tupelo, Miss., June 1st with a picked command of 2,400 men and two batteries, leaving only a small force in Mississippi. He got as far as Russellville, Ala., where Gen. Lee stopped him with another order on June 3rd, to return immediately to Tupelo, Miss., to meet Gen. Sturgis’s expedition, which was marching into Mississippi. Gen. Lee at the same time ordered Gen. Roddey to reinforce Gen. Forrest in Mississippi, as the column that had started from Decatur had moved eastward to reinforce Gen. Sherman in Georgia. Gen. Chalmers’ division was still left in Alabama; but later, McCullough’s brigade was ordered back into Mississippi to reinforce Gen. Forrest.

The delay in starting the expedition from Memphis caused Gen. Forrest to believe it was not coming; and in his telegram of May 20th (p. 628, Serial Number No. 78 Rebellion Records) he said that, “The time has arrived, if I can be spared and allowed 2,000 picked men from Buford’s division, will attempt to cut enemies communication in Middle Tennessee.” But the movement of a column of 8,000 men from Decatur, Ala., southward, which proved to be a feint in favor of Gen. Sturgis, caused Gen. Lee (May 31st) to order Gen. Forrest to move with “his disposable force” to help Gen. Roddey in resisting this column. Gen. Forrest left Tupelo, Miss., June 1st with a picked command of 2,400 men and two batteries, leaving only a small force in Mississippi. He got as far as Russellville, Ala., where Gen. Lee stopped him with another order on June 3rd, to return immediately to Tupelo, Miss., to meet Gen. Sturgis’s expedition, which was marching into Mississippi. Gen. Lee at the same time ordered Gen. Roddey to reinforce Gen. Forrest in Mississippi, as the column that had started from Decatur had moved eastward to reinforce Gen. Sherman in Georgia. Gen. Chalmers’ division was still left in Alabama; but later, McCullough’s brigade was ordered back into Mississippi to reinforce Gen. Forrest.

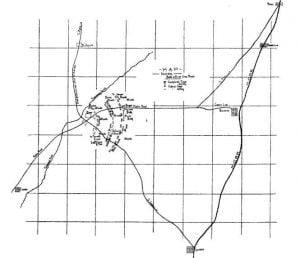

The army of Gen. Sturgis was most carefully organized and equipped, and was intended to defeat and crush Gen. Forrest, to destroy the railroads south of Corinth, and to penetrate as far into Mississippi as Columbus and Macon, returning thence by way of Grenada, Miss., to Memphis. It was made up of a division of cavalry commanded by Gen. Grierson, composed of two brigades. one commanded by Col. Waring (1,500 men), the other by Col. Winslow (1,800 men). The infantry division under Col. McMillan’s command was composed of three brigades, which were commanded by Col. Wilkins (2,000 men), Col. Hoge (1,600 men), and Col. Bouton (negro brigade,1,200 men) in addition to 400 men, who had charge of 22 pieces of artillery. According to these figures the Federal force represented a total of 8.500 men, equipped and rationed for 20 davs, and accompanied by a train of 250 wagons. Gen. Sturgis left Lafayette, Tenn., June 2nd, and marched south of the railroad (M. & O.), via. Salem and Ruckersville, reaching Ruckersvillc on June 6th. One of his brigades, which was detached, struck the railroad at Rienza, 10 miles south of Corinth. This indicated that the column might be going by Corinth to reinforce Gen. Sherman in Georgia. Here Gen. Sturgis abandoned his plan of moving as far north as the M. & O. railroad, and moved south to Ripley, Miss., at which point he took the Ripley and Guntown road in a southeasterly direction, encamping at Ripley on June 7th. He had been delayed by excessive rains and muddy roads, and reached Stubb’s farm, 16 miles from Ripley, on the night of June 9th. This place was also 9 miles from Brice’s Cross Roads, where the battle was fought. At this point, the road from Baldwin, Miss., to Pontotoc crossed the Ripley and Guntown road almost at right angles and made the “Cross Roads.” From the “Cross Roads,” it was 6 miles to Guntown and 5 miles to Baldwin each on the M. & O railroad. The country was slightly undulating and thickly wooded, with little cleared ground.

Gen. Forrest, on receiving the order at Russelville, Ala., promptly retraced his steps, arriving at Tupelo on the evening of June 5th. He at once began to move his command into position, awaiting the development of the plans of the enemy. He learned that the enemy were at Ruckersville on June 6th, and that a brigade was also at Rienza. He moved Buford’s division first to Baldwin and then to Booneville and ordered Bell’s large brigade to Rienza. Rucker was at Booneville by Gen. Lee’s order. At Baldwin on the evening of June 9th, Gen. Forrest learned for the first time that the enemy had changed his plans, and had abandoned his northern route and was moving on the Ripley and Guntown road.

With the concurrence of Gen. Lee, he at once issued orders to move his troops rapidly to the southward, to get in front of Sturgis’s command, now that his plans were more fully developed. He hoped by a rapid movement to reach and pass Brice’s Cross Roads before the Federal army reached that point. Bell was at Rienza, 25 miles distant, and his artillery was at Booneville, 16 miles to the north. Rucker was also at Booneville, and Lyon’s and Johnson’s brigades were at Baldwin,Johnson’s brigade of Roddey’s command having just arrived. The enemy however was nearer the “Cross Roads” than was expected, having encamped, and concentrated at Stubbs’ farm on the Ripley and Guntown road on the night of the 9th, when Forrest first learned of the change of direction of the Federal column. But all that rapid marching and movement could accomplish was being done, and Forrest had his entire force in the vicinity of the “Cross Roads” by I p. m. next day, at which hour he had all his command up and in action. Forrest’s troops consisted of Bell’s brigade (2,787 men), Rucker’s brigade (700 men), Johnson’s brigade (500 men), Lyon’s brigade (800 men), a total of 4,787 men. He had two batteries of artillery. Gen. Lee and Gen. Forrest were together in consultation at Baldwin when a change of plans by the enemy was first known. It was decided that Forrest should throw his command rapidly in front of Gen. Sturgis, and if possible, draw him farther towards Okolona before fighting. This would enable Gen. Lee, the department commander, to get some additional reinforcements before delivering battle to a force known to be double the available force under Gen. Forrest. It was not certain that Gen. Forrest could get in front of Gen. Sturgis before reaching the “Cross Roads.” But he believed he could, and, to expedite matters, the wagon trains were moved southward on the east side of the M. & O. railroad, so as to leave the road clear for the rapid movement of the troops. In a letter of Jan. 3ist, 1902, Capt. Sam Donaldson (Gen. Forrest’s aide) says, “I remember full well that this consultation was of the most pleasant kind, and that the next day much to the surprise of Gen. Forrest, the commands of Grier son and Sturgis appeared in force, and the great battle of Tishomingo Creek was fought that afternoon.” Gen. Lee, early on the morning of June 10th, went by rail to Okolona, both he and Gen. Forrest believing the enemy sufficiently far off to enable all the troops to get by the “Cross Roads” before the enemy arrived at that point.

With the concurrence of Gen. Lee, he at once issued orders to move his troops rapidly to the southward, to get in front of Sturgis’s command, now that his plans were more fully developed. He hoped by a rapid movement to reach and pass Brice’s Cross Roads before the Federal army reached that point. Bell was at Rienza, 25 miles distant, and his artillery was at Booneville, 16 miles to the north. Rucker was also at Booneville, and Lyon’s and Johnson’s brigades were at Baldwin,Johnson’s brigade of Roddey’s command having just arrived. The enemy however was nearer the “Cross Roads” than was expected, having encamped, and concentrated at Stubbs’ farm on the Ripley and Guntown road on the night of the 9th, when Forrest first learned of the change of direction of the Federal column. But all that rapid marching and movement could accomplish was being done, and Forrest had his entire force in the vicinity of the “Cross Roads” by I p. m. next day, at which hour he had all his command up and in action. Forrest’s troops consisted of Bell’s brigade (2,787 men), Rucker’s brigade (700 men), Johnson’s brigade (500 men), Lyon’s brigade (800 men), a total of 4,787 men. He had two batteries of artillery. Gen. Lee and Gen. Forrest were together in consultation at Baldwin when a change of plans by the enemy was first known. It was decided that Forrest should throw his command rapidly in front of Gen. Sturgis, and if possible, draw him farther towards Okolona before fighting. This would enable Gen. Lee, the department commander, to get some additional reinforcements before delivering battle to a force known to be double the available force under Gen. Forrest. It was not certain that Gen. Forrest could get in front of Gen. Sturgis before reaching the “Cross Roads.” But he believed he could, and, to expedite matters, the wagon trains were moved southward on the east side of the M. & O. railroad, so as to leave the road clear for the rapid movement of the troops. In a letter of Jan. 3ist, 1902, Capt. Sam Donaldson (Gen. Forrest’s aide) says, “I remember full well that this consultation was of the most pleasant kind, and that the next day much to the surprise of Gen. Forrest, the commands of Grier son and Sturgis appeared in force, and the great battle of Tishomingo Creek was fought that afternoon.” Gen. Lee, early on the morning of June 10th, went by rail to Okolona, both he and Gen. Forrest believing the enemy sufficiently far off to enable all the troops to get by the “Cross Roads” before the enemy arrived at that point.

At 10 a. m., June 10th, Gen. Forrest telegraphed Gen. Lee at Okolona from Baldwin (p. 645, Serial No. 78 Rebellion Records) :

“Enemy are advancing directly on this place ; Johnson’s brigade is here ; Buford’s division and Rucker’s brigade with two batteries will be here by 12 o’clock; our pickets have already commenced firing. N. B. Forrest, Major General. I have signed this for the general who directed it sent down by the train. He has moved himself. Chas. W. Anderson, Aide-de-Camp.”

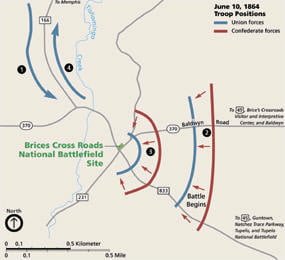

The three brigades of Lyon, Rucker, and Johnson were near at hand, while the largest brigade (Bell’s) and the artillery were at considerable distance; all moving on a road almost parallel with the railroad and nearer to it than the road by which the enemy were approaching it. Gen. Forrest with that decision, for which he was remarkable, as he found the enemy across his path, decided to give battle at once, with the troops he had. Lyon’s brigade was in front, followed by Rucker’s and Johnson’s, with the other troops moving rapidly up. He learned the enemy’s cavalry was near the “Cross Roads,” and would reach that place before he got there, but his scouts began skirmishing west of the “Cross Roads.” The enemy reached the roads and formed a line of battle, almost a mile from it on the Baldwin and Guntown roads, having more of a defensive than aggressive spirit.

Gen. Sturgis had sent back to Memphis about 400 disabled men before reaching Stubbs’ farm, which made his force about 8,100 men. Gen. Grierson, early on the morning of June loth, at 5.30 a. m., put his cavalry division in motion towards the “Cross Roads,” 9 miles distant. He soon struck Gen. Forrest’s scouts, driving them rapidly before him. On reaching the intersection of the roads, he sent strong scouting parties towards Baldwin and Guntown. He met the head of Forrest’s column on the Baldwin road, about a mile from the “Cross Roads” about 10 a. m. and at once formed Waring’s brigade in line of battle on both sides of the road and covering it. He also moved up Winslow’s brigade and put it on the right of Waring’s, extending to and covering the Guntown road. He reported meeting the enemy to Gen. Sturgis, who did not start his infantry division till after 7 o’clock. His trains were still further delayed by the bad roads. The infantry under urgent requests, was hurried up, but did not arrive on the field until about 2 o’clock. In the meantime Gen. Grierson became hotly engaged, and although he fought the Confederates from 10 a. m. until 2 p. m. with variable success, he was gradually driven back, and his ammunition was almost exhausted, so that before the head of the infantry arrived on the field, the cavalry was very nearly defeated. Gen. Grierson asked Gen. Sturgis to permit him to withdraw, and move his cavalry to the rear to reorganize and replenish his ammunition as soon as he could be relieved by the infantry. It was so ordered.

The infantry of the Federals arrived almost exhausted. The leading brigade (Hoge’s) was at once formed in the rear of Waring, who had already been pressed back about 400 yards on the Baldwin road. The second brigade (Wilkin’s) arrived immediately after the first had been put in line, and it was put immediately on the right of Hoge, relieving Winslow’s brigade and covering the Guntown road, while the 3rd brigade (Bouton’s) remained further to the rear to guard the numerous wagon trains, which had crossed Tishomingo creek. The fighting slackened a little as the infantry relieved the cavalry, which moved rapidly to the rear, after having been engaged in hard fighting from 10 a. m. till 2 p. m., during which time it had been gradually pressed back by the Confederates. The artillery, owing to the dense wood, could only be used at times. A battery had been put on the Baldwin road. The remainder of the artillery was generally massed near the “Cross Roads” and, as was usual with the Federal Army, the lines of battle were double. The infantry had scarcely got into position (about 2 p. m.) before the confederates made a most furious attack from right to left. Two batteries opened with telling effect on the Baldwin road, the shot falling thick and fast all about the “Cross Roads,” among the artillery and reserves, while the fire of the small arms of the confederates was most rapid and telling. This severe fighting continued for over two and a half hours. It was most desperate, and although the Confederates were several times driven back, they recovered themselves, and gradually pressed the infantry line back to the “Cross Roads,” until it gave way in utter confusion, pressing towards the bridge over Tishomingo creek, but a short distance in the rear of the battle field. To increase the panic, the Confederates appeared on both flanks about the time the infantry relieved the cavalry, creating great uneasiness as to the safety of the trains and the rear of the army, guarded by the negro brigade under Col. Bouton. Gen. Sturgis and Col. McMillan, who commanded the infantry division, behaved heroically as did their subordinates, but they could not stem the disaster in face of the most rapid and persistent fighting of the Confederates all along their front and flanks. The defeat soon became a rout. The negro brigade was soon disposed of, and the artillery and trains in inextricable confusion gradually fell into the hands of the Confederates. All organization was virtually lost after a vigorous pursuit of a few miles. Unsuccessful attempts were made to reform the line near the trains about dark, at Dr. Agnew’s plantation, but a disposition on the part of every one to move to the rear rendered these attempts fruitless. A partial reorganization was attempted at Ripley, the next morning (11th of June). The Confederates still pressed the rapid retreat towards the railroad, which stopped at LaFayette. From this place the expedition had started and at it Gen. Sturgis was met by reinforcements from Memphis. The expedition was ten days reaching the battle field, but it returned over the same distance in one day and two-nights. Many stragglers escaped from the Confederates and, after wandering through the country, reached the M. & C. railroad several days later.

Gen. Forrest, having decided to engage in battle, displayed great skill in handling his troops and in hurrying them up. The three brigades near Baldwin (Lyon’s, Rucker’s, and Johnson’s) numbered 2,000 men, and when dismounted could number little over i, 600 men. With this force he met the advance of Gen. Grierson on the Baldwin road about 10 a. m. Lyon’s brigade, which was in front, dismounted and formed into line of battle on both sides of the road. Lyon’s brigade was aggressive or defensive as circumstances indicated, but it was fighting all the time. Forrest himself led Rucker’s brigade as it came up. Dismounting a part of it, he removed the rest further to the left, and placed it on Lyon’s left, stretching it towards the Guntown road. Having ordered a regiment sent to the rear of the enemy, north of the road upon which he was moving early in the morning, he sent his escort company and another company around on the extreme left (the Federals’ extreme right). This disposition of the troops made the Federals believe he had a larger force than he really had. He then put Johnson’s brigade to the right of Lyon’s and on the west side of the Baldwin road. As has been stated, Bell, with his larger brigade, was hurrying by a forced march from Rienza (25 miles) and his artillery was rapidly coming up (16 miles) over the bad roads. They did not arrive, however, until after i o’clock. In the meantime, Gen. Forrest was savagely fighting with less than 2,000 men the 3,300 cavalry under Gen. Grierson.

The fighting was most severe, and was conducted with varying success for about three and a half or four hours, and when the infantry of the Federals and Bell and the artillery, the last of Forest’s command, arrived on the field, the cavalry of Gen. Grierson had been whipped and were clamoring to be relieved. Waring had already been pressed back by Lyon and Johnson to his second line of battle, about 400 yards. Gen. Sturgis, having arrived on the field, Winslow urged to be relieved, and Gen. Grierson earnestly requesting to be allowed to withdraw his cavalry to be reorganized and re-supplied with ammunition. The placing of the infantry of the Federals, when the cavalry had been fighting for nearly four hours, for a short time stemmed the current of disaster. But before they were entirely in line and the cavalry out of the way (almost in disorder) Gen. Bell arrived with his large brigade and Major Morton with his two batteries. It was the critical hour of the battle. Forrest placed two batteries of artillery on the Baldwin road, and opened a furious cannonade, the effect of which was soon visible. At the same time Gen. Forrest took Bell’s brigade and carried it to the extreme left of his line. This fresh arrival at once restored the fortunes of the day in favor of the Confederates, but not without a severe conflict of over two hours, at which time (4.30 p. m.) the entire Union line was being gradually pressed back. The enemy began to break badly. A stand was attempted on a short line near the “Cross Roads,” but Forrest gradually pressed around them, being encouraged by the evident discomfiture of the enemy. The artillery was pressed forward and fought at close range. At the same time the regiment to the north and near the rear of the enemy, and the companies to the rear and south, had created almost a panic. Soon the entire command of the enemy gave way. The trains and artillery blocked the bridge over Tishomingo creek, so that the enemy had to wade the stream. Confusion was soon evident everywhere, and disorder reigned. Forrest then had the bridge over Tishomingo creek cleared by throwing wagons and dead animals into the stream. He crossed his artillery and some of his cavalry, and pressed the enemy vigorously. The confusion was increased and the artillery and wagons of the enemy gradually fell into his hands ; some of his guns being captured at the “Cross Roads.” The others and the wagons were captured in Hatchie “bottom.” He pursued the enemy to Lafayette, Tenn., from which place they had started on June 1st. It was simply a matter of endurance of men and horses that saved the entire command from being captured. Forrest had just returned from Alabama and his horses were jaded by the rapid marching and countermarching before the battle, while the enemy were comparatively fresh from their slow progress and short marches daily. The Federals also, when they saw the inevitable, cut out the horses and mules from the artillery and wagon trains, mounted them and were enabled to get out of the way more expeditiously than they otherwise could have done. These animals, numbering near 2,000, added to Grierson’s cavalry made about 5,000 men mounted out of the 8,000 engaged in the battle. When we consider that over 2,000 were killed or captured and 3,000 stands of arms left on the field, it leaves only about one thousand who had to make their way back on foot. Many of those who were mounted were unencumbered by arms.

This battle and victory of Gen. Forrest deservedly gave him a great reputation and was one of the most complete victories of the war. The fruits of the battle as shown in Gen. Forrest’s address to his men under date of June 28th, 1864, were 17 guns, 250 wagons, 3,000 stands of arms, and 2,000 prisoners. It is likely however that the loss in men of the enemy did not exceed 2,168, all told. Forrest’s own loss was 493 men killed and wounded. It may be fairly stated that taking out the horse holders and guards for the trains, Forrest never had over 3,500 men available in the battle, against 8,100 men of the enemy.

Back to: Mississippi History